Facts About Meteor Showers

- The majority of meteor showers are caused when Earth moves through the debris stream of an orbiting comet.

- Two known meteor showers are from the debris of asteroids rather than comets. The Quadrantids shower is believed to be from the minor planet 2003 EH1. The other one, the Geminid meteor shower, is from an asteroid called 3200 Phaethon.

- The Orionid Meteor shower is a result of dust and debris from the famous Comet 1P/Halley. It happens in late October every year.

- A study by Nature in 1985 looked into how rare it was for a human to be struck by a meteorite. The study estimated that a meteorite would strike a person once every 180 years—an average of 0.0055 per year. Ann Hodges, in 1954, is the only confirmed case of this. This would suggest that another person won’t be struck until 2134.

- The earliest recorded of the annual Perseid meteor shower is found in Chinese annals from 36 AD.

- The best time to view a meteor shower is in the early hours of the morning with a dark night and a moonless sky. Some showers, like the Leonids, are best viewed in the North.

- Some meteor showers, such as the Alpha Monocerotids do not happen every year. But when they do they can be very impressive!

We can see a few meteors on any given night. However, they are not easy to observe and not very bright. When there are lots of these meteors together, that is when we see a meteor shower.

What is a meteor shower?

Meteor showers are typically associated with comets. When a comet orbits the Sun, it sheds a stream of dusty and icy debris along its orbit path. If Earth happens to be traveling through this stream, it reacts to our atmosphere and a meteor shower happens. The Earth passes through these debris trails as it orbits the Sun. Because of that, we can see some meteor showers yearly.

The meteors can appear anywhere in the sky. However, if you trace their path back up they appear to “rain” in from the same area of the sky. Usually, these showers are named for the constellation that coincides with this region. We call this spot the “radiant.”

For example, the Leonid meteor shower has its radiant in the constellation Leo. Also, the Perseid meteor shower is named so because the meteors appear to fall from a point in the Perseus constellation.

The number of meteors we see during peak activity is called the zenithal hourly rate (ZHR). Some meteor showers have a ZHR of only a few meteors while others have about a hundred.

Meteor showers in 2021

| Name | Date of Peak | Activity Period |

|---|---|---|

| Quadrantids | Night of January 2/3 | Dec 26-Jan 16 |

| Lyrids | Night of April 21/22 | Apr 15-Apr 29 |

| Eta Aquarids | Night of May 4/5 | Apr 15-May 27 |

| Perseids | Night of August 11/12 | Jul 14-Sep 1 |

| Orionids | Night of October 21/22 | Oct 02-Nov 07 |

| Leonids | Nights of November 16/17 | Nov 06-Nov 30 |

| Southern Taurids | Night of October 9/10 | Sep 10–Nov 20 |

| Northern Taurids | Night of November 11/12 | Oct 20–Dec 10 |

| Geminids | Night of December 13 | Nov 30-Dec 17 |

| Ursids | Night of December 22 | Dec 17-Dec 24 |

What are shooting stars?

We often use the terms “shooting stars” and “falling stars” to describe meteors. The bright streaks of light across the night sky are caused by small pieces of interplanetary rock and debris called meteoroids. They also orbit the Sun just like the planets, asteroids, and comets do.

Meteoroids are objects floating in space. We can think of them as “space rocks” blasted off from bigger bodies. Many of them are produced in the asteroid belt, the area between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter. They form when asteroids collide and smash into each other.

Many meteoroids are also formed from the debris left by comets. Like dirty snowballs, comets are icy objects that release gas and dust as they move towards the Sun. Hundreds of meteoroids are produced from the material that comets shed.

Aside from comets and asteroids, some meteoroids are known to come from the Moon and the red planet, Mars.

Composition

The compositions of meteoroids differ from each other because they come from different sources. Some of them are rich in metal while others are rocky. Some are rocky and metallic at the same time.

Since they are fragments of larger bodies, meteoroids are generally smaller than asteroids and comets. Some of them can be as small as dust, called micrometeoroids. The largest of them can be the same size as small asteroids.

The Earth comes across these meteoroids as it journeys around the Sun. When they enter our atmosphere, we call them meteors. These meteors burn up under the intense friction of Earth’s atmosphere some 30 to 80 miles above the ground. They travel tens of thousands of miles per hour. Because of that, most of them are completely burned up by the atmosphere. The 500 or so per year that reach the ground are called meteorites.

When we see a meteor, it appears to “shoot” at great speed across the sky. With its brightness and intensity, we might think it’s a star rather than a falling piece of rock.

Review: Meteoroids, Meteors, Meteorites

Shooting stars begin their lives with the violent bang from collisions and comets burning up. Though they are basically the same thing, we call them differently throughout their journey.

The fragments that float through space are called meteoroids. By the time they enter the Earth’s atmosphere, we call them meteors. We usually call meteors “shooting stars” because they burn up and produce bright light displays across our sky.

Some meteors totally disintegrate during this trip. However, some of them reach the ground, and this time, we call them meteorites.

Famous meteor showers

There are plenty of famous meteor showers that are easy to observe. We can see a lot of them throughout the year. Sometimes, they have very bright meteors called “fireballs.” Let’s get to know these meteor showers so we can see them by the time they visit our night sky.

Quadrantids

- Origin: 2003 EH1

- Radiant: Bootes constellation

- Meteor Count (peak): Around 80 meteors per hour

- Meteor Velocity: 41 kilometers (25.5 miles) per second

- Activity Period: December 26 – January 16

The Quadrantid meteor shower is one of the first light shows that we see at the beginning of the year. It occurs from December 26 to January 16 and peaks around January 3.

The Quadrantids have been observed for a long time and were discovered around the 1820s. Its point of origin or radiant is in the constellation of Boötes (the Herdsman). This is a northern constellation that sits below the Big Dipper and above the Draco constellation (the Dragon).

The Quadrantid meteor shower can produce around 80 meteors in the sky like the Perseids and the Geminids. However, its peak time does not last very long. It only lasts for hours while the other two can go on for days.

With its location, the Quadrantid meteor shower is best seen in the northern hemisphere. Still, it can also be seen at latitudes 50 degrees south and up. In the northeastern sky, the radiant appears above the horizon after midnight. That said, the best time to see it is on the night of January 2 to the dawn of the next day.

In 2003, astronomer Peter Jenniskens proposed the asteroid 2003 EH1 as the parent body of the Quadrantids. Later, it was found to be linked to the C/1490 Y1 comet.

The Quadrantid meteor shower is named after the now-obsolete constellation called Quadrans Muralis (mural quadrant). It was created in 1795 by astronomer Jérôme Lalande but was defunct in 1922.

Lyrids

- Origin: C/1861 G1 Thatcher

- Radiant: Lyra constellation

- Meteor Count (peak): 20 meteors per hour

- Meteor Velocity: 49 kilometers (30 miles) per second

- Activity Period: April 16 – April 25

The Lyrid meteor shower occurs every year from April 16 to 25. It usually peaks around April 21 or 22 with about 20 meteors per hour.

The Lyrids have been observed as early as 687 BC. They are the debris of the comet C/1861 G1/Thatcher. These meteors radiate from the constellation of Lyra (the Lyre). We can easily sport it because it is close to Vega, the brightest star in the constellation.

Though not generally strong, the Lyrids sometimes surprise us with surges of as many as 100 meteors per hour. Their apparent magnitudes are usually around 2.0. Another thing that makes the Lyrid meteor showers exciting are the occasional fireballs. These meteors are exceptionally brighter than the others.

Observers from the northern hemisphere are at the front seat of viewing the Lyrids. We can seem best in rural areas away from the city lights where there is not much light pollution. Generally, the Lyrids rise at around 3 AM in late April, after the setting of the moon and before dawn.

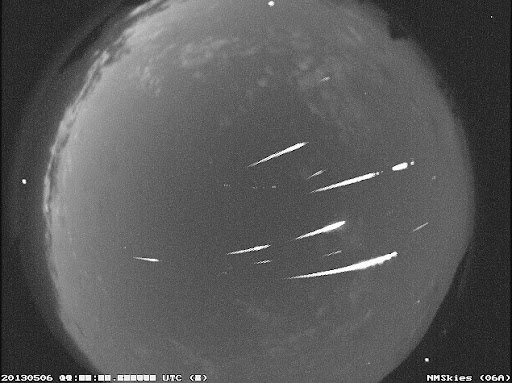

Eta Aquarids

- Origin: Halley’s Comet (1/P Halley)

- Radiant: Aquarius constellation

- Meteor Count (peak): About 10 to 20 meteors per hour

- Meteor Velocity: 66 kilometers (41 miles) per second

- Activity Period: April 19–May 28

The Eta Aquarids, also spelled Eta Aquariids, radiate from the constellation of Aquarius (the Water Bearer). The Delta Aquarids (also Delta Aquariids) seem to originate from the same constellation too but at a different point.

The Eta Aquarid meteor shower occurs from April 19 to May 28 each year. It peaks just hours before the dawn of May 5. Observers from the northern and the southern hemispheres can observe this light show. However, it is best seen in the southern hemisphere. From the northern sky, Eta Aquarids look more like “earthgrazers.” Earthgrazers are meteors that skim the Earth’s atmosphere and leave again.

We can usually see about 20 Eta Aquarids per hour. They are fast-moving meteors that travel around 66 km/s. Because of this, they leave luminescent streaks behind called “trains.”

The parent body of the Eta Aquarids is the famous Halley’s Comet. They are thought to be debris that separated from the comet hundreds of years ago.

Perseids

- Origin: 109P/Swift-Tuttle

- Radiant: Perseus constellation

- Meteor Count (peak): Up to 100 meteors per hour

- Meteor Velocity: 59 kilometers (37 miles) per second

- Activity Period: July 14–August 24

The Perseid meteor shower happens when Earth moves through the debris stream of the comet 109P/Swift-Tuttle. We can see it in mid-August for most of the night. It peaks around August 11 to 12.

The Perseids are called the best meteor shower by many. This rich meteor shower rains about 50 to 100 meteors per hour. But not only that—they are also bright and fast-moving. We can observe a lot of fireballs during this shower, with apparent magnitudes around -3. Compared to smaller meteors, fireballs leave brighter trains of light and color.

Observing the Perseids is very ideal since they occur during the summer. Also, we do not need exceptionally dark and clear skies to witness them. They are best seen in the northern hemisphere. There are times when you can see them as early as 10 pm. But if you want to see the most meteors, you should wait around late evening to dawn.

The Perseids have their radiant from the constellation Perseus (the Hero). They are the debris left by the comet periodic comet Swift–Tuttle. It completes a journey around the Sun in 133 years.

Orionids

- Origin: Halley’s Comet (1P/Halley)

- Radiant: Orion constellation

- Meteor Count (peak): About 15 meteors per hour

- Meteor Velocity: 66 kilometers (41 miles) per second

- Activity Period: October 2–November 7

The Orionid meteor shower is another event associated with Halley’s Comet. It occurs from October 2 to November 7 and peaks on October 21.

The Orionids are bright and swift, racing through our sky 66 kilometers (41 miles) per second. Because of that, they leave behind luminous streaks that last for several minutes. We can see these meteors over a large area of our night sky. On some nights, we might also get a glimpse of some fireballs.

The Orionids radiate from the constellation of Orion (the Hunter). Specifically, these meteors appear to come from the asterism of the hunter’s club, north of the star Betelgeuse.

The Orion constellation is located on the celestial equator. This location allows stargazers from the northern and southern hemispheres to see the Orionids. The best time to wait for them is around mid-October, just hours before dawn.

The parent body of the Orionids, Halley’s Comet, orbits the Sun once every 76. It is also the source of the Eta Aquarids.

Southern Taurids

- Origin: Encke’s Comet (2P/Encke)

- Radiant: Taurus constellation

- Meteor Count (peak): About 5 meteors per hour

- Meteor Velocity: 28 kilometers (17 miles) per second

- Activity Period: September 10–November 20

The Taurids are two different meteor showers: the Southern Taurids and the Northern Taurids. They are often called the “Halloween fireballs” because they occur around the time of Halloween. Also, these meteor showers can overlap with each other.

The Southern Taurids are active around September to mid-November. This shower has a long activity period. This is because the streams responsible for the meteors are very diffuse. They are widely dispersed because of the perturbations of other planets, particularly Jupiter.

The Southern Taurid meteor shower peaks on October 10. It is observable in both the northern and southern hemispheres. We can see it best around the late night of October 9 until the dawn of October 10.

The Southern Taurids is a weak shower with only about 5 meteors per hour. Since they are not very bright, we can see them better in a dark, moonless sky.

The parent body of the Southern Taurids is the Comet Encke. This comet is believed to be from an even bigger body that broke into pieces about 20,000 years ago.

Northern Taurids

Origin: 2004 TG10

Radiant: Taurus constellation

Meteor Count (peak): About 5 meteors per hour

Meteor Velocity: 29 kilometers (18 miles) per second

Activity Period: October 20–December 10

The Northern Taurids is another meteor shower that appears to come from the Taurus constellation (the Bull). It only produces about 5 meteors per hour. Still, they are worth checking out because they can produce fireballs.

Skywatchers can enjoy the Northern Taurids from mid-October to December 10. Like the Southern Taurids, the Northern Taurids also have a long activity period. Since the debris stream is rather spread out in space, it takes the Earth some time to move across it.

Northern Taurids are best viewed in the late evening of November 11 until the dawn of November 12. We can see them best under a dark sky. These meteors are not very fast-moving, with a velocity of around 29 kilometers (18 miles) per second.

The streams that produce the Northern Taurids are from the asteroid 2004 TG10. This object is also the source of the Beta Taurids, a “daytime shower” that occurs in June. The 2004 TG10 itself is believed to be from the bigger Comet Encke.

Leonids

- Origin: 55P/Tempel-Tuttle

- Radiant: Leo constellation

- Meteor Count (peak): About 15 meteors per hour

- Meteor Velocity: 71 kilometers (44 miles) per second

- Activity Period: November 6–November 30

We can see the Leonid meteor shower from early to late November. Though generally it only has about 15 meteors per hour, it is still considered a major shower. It becomes a busy one every 33 to 34 years because it produces a meteor storm.

While the strongest meteor showers have about a hundred meteors per hour, meteor storms can have thousands. Thousands of these meteors shoot through the sky in the Leonid storm of 1966. Meanwhile, the earliest record of Leonids dates back to 902 AD.

In the night sky, the Leonids seem to radiate from a point in the Leo constellation (the Lion). These meteors are from the 55P/Tempel-Tuttle comet. This comet has an orbital period of 33 years around the Sun.

The Leonid meteor shower produces fast-moving meteors moving roughly 71 kilometers (44 miles) per second. There are also fireball and earthgrazer Leonids which are both bright and colorful.

We can see the Leonids best in the late night of December 16 to early December 17. It is best viewed from the north where the celestial lion rises. Those who want to witness this meteor shower should consider the cold winter weather outside.

Geminids

- Origin: 3200 Phaethon

- Radiant: Gemini constellation

- Meteor Count (peak): About 120 meteors per hour

- Meteor Velocity: 35 kilometers (22 miles) per second

- Activity Period: December 4–December 17

The Geminids meteor shower happens when the Earth crosses a stream from 3200 Phaethon. It occurs every year from early to mid-December.

The Geminids produce a rich shower, ranging from 50 to 120 meteors per hour. These meteors are not only numerous, but they are also very bright. They remain visible even when the shower is not very intense. They usually have a yellowish hue.

The Geminids appear to radiate from the direction of the Gemini constellation (the Twins). This point in the sky is near the brightest stars in the constellation, Pollux and Castor.

The meteor shower peaks on the night of December 13 until the Dawn of December 14. We can see them as early as 9 or 10 PM. Specifically, we can see the most Geminids around 2 AM, when the point of origin is highest in the sky. This spectacular display is visible to all observers from both hemispheres.

The origin of the Geminids is the asteroid 3200 Phaethon. This object orbits the Sun every 1.4 years.

Ursids

- Origin: Tuttle’s Comet (8P/Tuttle)

- Radiant: Ursa Minor constellation

- Meteor Count (peak): 10 meteors per hour

- Meteor Velocity: 33 kilometers (21 miles) per second

- Activity Period: December 17–December 26

One of the last light displays we see in a year is the Ursid meteor shower. This is an annual event that is active from December 17 to 26.

The Ursids are not particularly spectacular. We can only see about 5 to 10 meteors per hour during its peak. It has a narrow peak that lasts only about 12 hours. Because of that, scientists believe that the streams responsible for the meteors are not very spread out.

The radiant of the Ursids seems to come from the constellation of Ursa Minor (the Little Bear). This point appears to be near the brightest star in the constellation, Kochab. We can see it best around the pre-dawn hours of December 22, in the northern hemisphere. Skywatchers should prepare for the winter temperature outside though.

The steams that produce the Ursids are from Tuttle’s Comet. This object takes 13.6 years to orbit the Sun.

More Fun Meteor shower facts

- There are approximately 30 meteor showers visible to us on Earth each year.

- Fireballs are exceptionally bright meteors that are even brighter than the planet Venus. While Venus has an apparent magnitude of -4.14, fireballs can reach up to magnitude -3.

- The Lyrid meteor shower becomes more intense every 60 years. This is because the planets direct the dust trail of comet C/1861 G1 Thatcher into Earth’s orbital path.

- Aside from the Earth, other astronomical bodies in the solar system also experience meteor showers. However, the resulting light shows will be different depending on their atmospheres.

- Meteoroids and micrometeoroids can collide with man-made spacecraft in space. Because of that, these spacecraft use shields like the Whipple shield. The International Space Station has about a hundred of them.

- More than 60,000 meteorites have been found on Earth. Some of the rarest of them are meteorites from the Moon and Mars. Out of the total number, only about 126 of them are from Mars.

- Because they are rare, lunar and Martian meteorites are also very expensive. They are often sold in small slices. According to geology.com, these rare objects can cost around $1,000 per gram or even more. They cost way much higher than gold.

Sources:

https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/asteroids-comets-and-meteors/meteors-and-meteorites/in-depth/

(https://earthsky.org/astronomy-essentials/earthskys-meteor-shower-guide/)

https://www.nasa.gov/pdf/741990main_ten_meteor_facts.pdf

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Meteoroid

https://blogs.nasa.gov/Watch_the_Skies/tag/taurid-meteor/

Image Sources:

Meteor showers: https://images.unsplash.com/photo-1532053413580-98b455b68458?ixid=MnwxMjA3fDB8MHxwaG90by1wYWdlfHx8fGVufDB8fHx8&ixlib=rb-1.2.1&auto=format&fit=crop&w=1170&q=80

Shooting stars: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/e/ed/Meteor_falling_courtesy_NASA.gif

Meteoroids, Meteors, Meteorites: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/6/63/Meteoroid_meteor_meteorite.gif

Quadrantids: https://apod.nasa.gov/apod/image/1901/Cuadrantidas30estelasDLopez1024.jpg

Lyrids: https://apod.nasa.gov/apod/image/2005/Lyrids_Horalek_960_annotated.jpg

Eta Aquarids: https://blogs.nasa.gov/Watch_the_Skies/wp-content/uploads/sites/193/2013/05/1037759main_eta.jpg

Perseids: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a1/Perseid_meteor_shower.jpg/1280px-Perseid_meteor_shower.jpg

Orionids: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b2/Orionid_Meteor%281%29.JPG/1280px-Orionid_Meteor%281%29.JPG

Southern Taurids: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/02/Taurid_Meteor_Shower_-_Joshua_Tree%2C_California_-_6_Nov._2015.jpg/1280px-Taurid_Meteor_Shower_-_Joshua_Tree%2C_California_-_6_Nov._2015.jpg

Northern Taurids: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/dd/Tauride-20201204.jpg/1280px-Tauride-20201204.jpg

Leonids: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a7/Leonid_Meteor.jpg/800px-Leonid_Meteor.jpg

Geminids: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/0d/Geminids.jpg/1200px-Geminids.jpg

Ursids: https://pbs.twimg.com/media/EpccJhYXEAEHSFq?format=jpg&name=900×900