The Visual Spectrum

To understand Fraunhofer lines, you need to understand the visual spectrum and how it reacts to gases. With continuous spectra, all of the wavelengths of the visible spectrum are visible. It’s what standard white light produces when it is dispersed through a prism. A good example of continuous spectra would be a rainbow.

On the opposite end of things, you have emissions. While all of the wavelengths of the visible spectrum can be seen with continuous spectra, emissions are a bit more distinct. Elements produce very specific wavelengths when the atoms are excited. As a result, each element gives off its own unique color. This does not change. The color remains constant, allowing scientists to easily identify the element based on the visible wavelengths its atom produces.

For example, sodium atoms generate a yellow light while mercury gives off blue and green light. Those distinct light emissions act like a signature or fingerprint for the elements.

How Fraunhofer Lines Are Created

Fraunhofer lines come into play when the continuous spectrum is affected by the gas. As the white light passes through a gas, those atoms will absorb some of the wavelengths. Can you guess which wavelengths are absorbed? Each gas atom will absorb the distinct wavelength, or color, that it gives off.

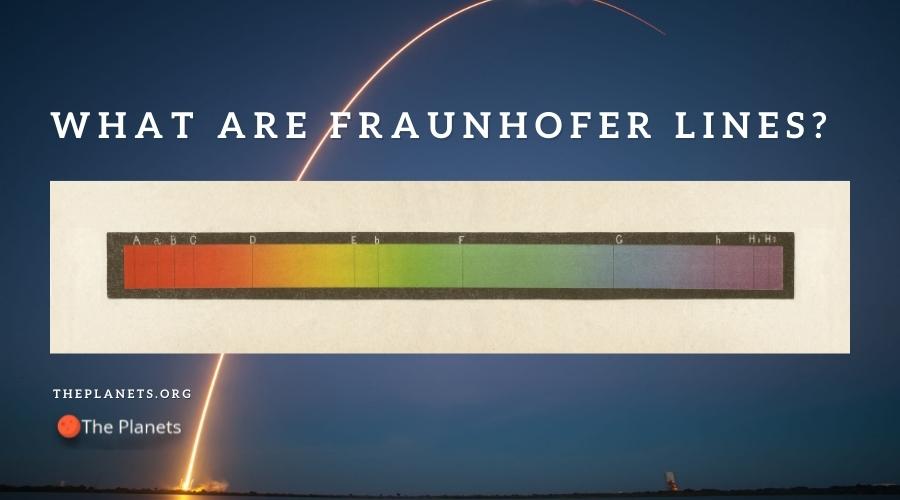

So, when the white light finally reaches its destination, the spectrum is not complete. It will be missing those absorbed wavelengths. When you look at the continuous spectrum, thick black lines will be present throughout. These are referred to as the Fraunhofer lines.

By taking note of what wavelengths were absorbed, scientists are able to determine what elements are present in the sun. In fact, the Fraunhofer lines led to the discovery of Helium. Back in 1870, Helium was an unknown element. All scientists knew at the time was that this element was found in the sun. It wasn’t until nearly 25 years later that the same element was discovered here on Earth.

To date, there are over 25,000 Fraunhofer lines on our solar system’s color spectrum. The lines are still being used today to study distant stars and other celestial bodies.